Image courtesy of the Charlotte Business Journal

In July of 2020, reporters discovered that Duke Energy had been in secret negotiations with at least sixteen other utilities to create SEEM — a bilateral trading market. Duke had maintained secrecy despite having been involved for months in a stakeholder process organized by North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper. When the negotiations came to light, Duke projected that SEEM might save North Carolina ratepayers around $10 million a year.

SEEM, as proposed, would be run by and for utilities. Customer and stakeholder engagement would be limited to an annual meeting along with the basic filings required at FERC. So far, utilities have made several presentations and answered questions in North Carolina, but to date, the rate paying public has not been invited to provide input or help shape the plan.

It was widely expected that FERC would let SEEM go forward with little fanfare, the standards for finding the plan ‘deficient’ being exceptionally low. To the surprise of many, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) issued a ten page letter of deficiency to utilities pursuing SEEM.

The irony of Duke Energy’s SEEM pursuit has not been lost on Carolinas ratepayers. Duke, which operates in several RTOs across the Midwest, uses hyperbolic language about the ‘dangers’ of generation markets. What more, the company recently gave half a million dollars to a dark money organization that attacked NC House leaders of both parties for even pursuing a bill to study utility reforms (House Bill 611).

Background

Through most of the 20th century, a majority of electricity customers in the United States received their energy through vertically integrated monopoly utilities—companies that own all levels of the energy supply chain, from generation to transmission and distribution. In the early 20th century, monopolies made sense: The first electric infrastructure required a great deal of capital and the market wasn’t yet structured for competitive electricity generation. Available utility technology required centralization.

In 1984, the Federal government broke up the AT&T monopoly, unlocking billions of dollars in new business opportunities and making innovation of the telecom products we enjoy today possible. Following suit in the 1990s, many states restructured their electric utility models. Some utilities divested from generation assets, created competitive retail markets for customers to choose their energy supplier, and encouraged an open-access arena for wholesale electricity trade.

Competitive generation benefits consumers in a host of ways. Independent power producers, which do not have highly paid executives and related overhead, can operate at lower margins than government regulated monopolies. Consumers also benefit because independent power producers take the risks that, if taken by utility, ultimately fall on the rate paying public. In the Carolinas, $9 billion nuclear plants that will never be finished along with another $9 billion in utility coal ash clean up are just two examples. Most of all, consumers benefit on cost when businesses compete to provide a service – rather than when a self interested bureaucracy makes a calculation and uses a rate payer supported platoon of attorneys and lobbyists to sell it to regulators.

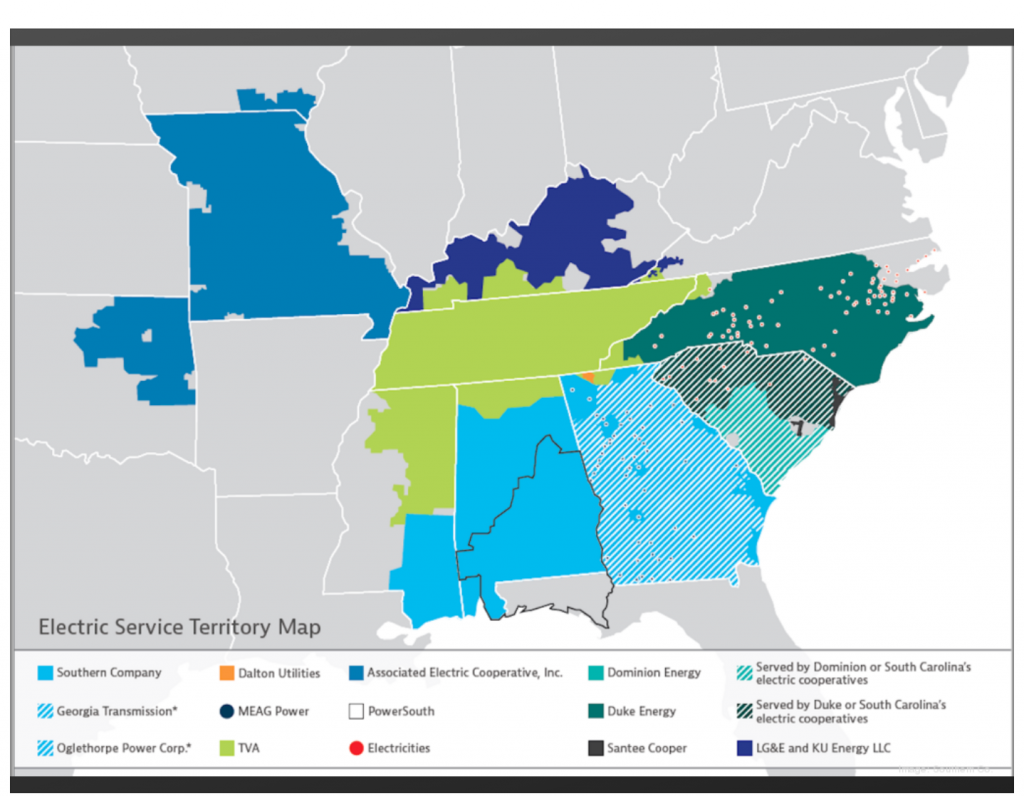

Monopolies in the Southeast

The Southeastern United States never took on the market reforms the rest of the country did. While most of the country was switching over to centralized dispatch energy markets, the Southeast retained the government regulated, vertically integrated utility model, leaving monopolistic utilities in charge of every aspect of the electricity supply chain. These utilities plan their electricity grids independently of neighboring grids, and power their service territories with an almost-complete lack of competition. Without competitors, utilities in the Southeast use their monopoly power to expand their rate base and continually raise rates — often despite flat energy demand. Government regulated monopolies have also been among some of the slowest to embrace modern electricity resources as they become more efficient and affordable.

Wholesale Markets

Wholesale markets have largely been operated as Energy Imbalance Markets (which are voluntary for utilities), and RTOs (regional transmission organizations) which comply with standards of transparency enforced by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). A 2019 study by the Brattle Institute showed that Duke Energy customers in North Carolina would have saved half a billion dollars a year if the company had been in the PJM RTO – more than half the cost of the Duke Energy coal ash spill cleanup in North Carolina over a decade.

RTOs are largely denoted by their independence from market participants, operational authority over transmission, set geographic scope and regional organization, and their exclusive ability to manage short-term grid reliability. RTOs balance electricity supply and demand in their day-ahead and real-time energy markets by committing least-cost resources in advance (in hourly increments) and then adjusting by dispatching real-time, least-cost resources every five minutes. This equates to lower marginal cost resources being dispatched first, and ultimately results in reliable electricity to consumers at the least cost possible. This also means that RTOs can promote greater renewable energy deployment, given lower marginal costs of wind and solar.

RTOs benefit ratepayers in several ways:

- They save on production costs by enhancing coordination between energy plants and utilizing lower costs or higher availabilities at particular plants;

- Enhanced coordination allows RTOs encompassing a larger geographic area to shift generated power around in response to variable needs in different locations. This also aids in limiting unnecessary capacity investments, as utilities can purchase wholesale electricity from other plants when demand is high, versus generating their own power (at a higher cost); and finally,

- Perhaps most important, RTOs provide stability and reliability across the transmission grid, coordinating across their singular transmission network to manage congestion and ensure adequate grid services are always available. Though Texas’ ERCOT is identified as a ‘market,’ it notably cuts itself off from power resources in other states, and thus has run short on capacity in critical weather situations.

Market Reform Shows Significant Savings

Two important studies by the Brattle Group and Vibrant Clean Energy show that an integrated market in the Southeast could save utilities as well as customers billions of dollars in the coming decades.

The Vibrant Clean Energy study notes that

- “The Southeastern RTO creates cumulative economic savings of approximately $384 billion by 2040 compared to the business-as-usual (BAU) case. In 2040, this amounts to average savings of approximately 2.5¢ per kilowatt-hour (kWh), or 29 percent in consumer electricity rates compared to BAU.”

The Brattle Group study concludes that

- “If Duke’s experience was the same as those of the utilities in PJM, then North Carolina customers could expect to receive benefits between $411 million per year and $593 million per year from Duke’s membership in an RTO market.”

Outside of the economic benefits noted above, membership in an RTO has other ancillary benefits. It could promote overbuilding power plants, increase efficiency via electricity trading, and introduce least-cost competition. An RTO could also create 285,000 new full-time jobs, reduce emissions by 37 percent, and create more market transparency throughout the region. Thus, there has been a lot of pressure on Southeastern utilities in recent years to try and create some type of market reform.

SEEM

Enter SEEM, the Southeast Energy Exchange Market. This proposal is simply an automated mechanism to speed trades between participating utilities. The participating utilities would be able to submit a bid to either provide to or purchase power from each other, and then an bilateral trading algorithm would automatically match together complementary companies.

Duke Energy forecast around $10 million in annual savings over the first few years of operation. Stakeholders have called the proposal a “pro-utility” model—more so than other market proposals—and noted SEEM would result in almost unnoticeable savings and benefits for customers when compared to more competitive structures.

In February of 2021, southeastern utilities filed a proposal with FERC to create SEEM. Filing members included:

- Alabama Power, Georgia Power Company, and Mississippi Power Company (collectively, “Southern Companies”);

- Associated Electric Cooperative, Inc. (“AECI”); Dalton Utilities (“Dalton”); Dominion Energy South Carolina, Inc. (“Dominion SC”);

- Duke Energy Carolinas, LLC (“DEC”) and Duke Energy Progress, LLC (“DEP”) with DEC and DEP collectively referred to as “Duke”;

- Louisville Gas & Electric Company (“LG&E”) and Kentucky Utilities Company (“KU”) collectively (“LG&E/KU”);

- North Carolina Municipal Power Agency Number 1 (“NCMPA Number 1”); Power South Energy Cooperative (“PowerSouth”);

- North Carolina Electric Membership Corporation (“NCEMC”); and

- Tennessee Valley Authority (“TVA”).

Other utilities are also interested in joining SEEM but were not officially part of the filing.

A number of non-profit advocacy groups and renewables companies came out in opposition to the preliminary filing, stating that SEEM (as proposed) would not be a good move for reducing energy costs or for spurring the transition to a clean energy economy. The Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA), Advanced Energy Economy (AEE), and others commented that SEEM could unlock customer benefits, but the proposal is deficient in important details. The Southern Alliance for Clean Energy and Southern Environmental Law Center also had their doubts, stating that the proposal could derail true market reform by strengthening utilities’ current position and planning, increasing their opportunities to exercise monopoly power and barring small or independent developers and projects from participation.

Ruling by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC)

Ultimately, FERC issued a 14 page response echoing stakeholder concerns, calling the proposal ‘deficient’ and noting that the SEEM plan as submitted might increase utilities’ chokehold on the market rather than spurring competition. FERC also held broader concerns about the proposal not including enough stakeholder support. The directive issued on May 4, 2021 outlined a detailed set of questions which will require utilities to provide very specific information on a variety of topics; queries include determining how SEEM the proposal would save customers money, how pricing would be set, what governance would look like (i.e. what standard of review would apply), how it would impact the existing Southeast power market, and if/how it would interact with RTOs like MISO, PJM, and SPP. In short, the utilities need more transparency and must provide more clarity on exactly how SEEM would influence (and if it would hurt or enhance) customer experience and broader market activity.

South Carolina’s Alternative Strategy

The SEEM proposal is not the only existing foray into the world of southeastern electricity market reform. In September 2020, the South Carolina General Assembly passed a study bill (HB 4940) to inform creation of a Southeast RTO. The bill was spurred by the failure of the VC Sumner nuclear plant, a $9 billion project that never came to fruition. In addition, South Carolinians were saddled with the highest electricity bills in the country—around $400 more than the U.S. average—and were looking at a 15% poverty rate, the 10th highest in the country.

The South Carolina Electricity Market Reform Measure Study Committee will be complete in 2021, with final results due for General Assembly review in 2022. The study results will provide specific detail about the potentially sweeping changes that may come from changing South Carolina’s electricity market, and will weigh consequences of utility generation/transmission divestiture, joining an existing RTO, creating a new RTO, creating an Energy Imbalance Market. Independent studies have shown that an RTO may yield more than four times the estimated annual SEEM benefits; the study’s overall goal is to determine which market conditions will best promote competition and allow South Carolinians to utilize least-cost power.

North Carolina’s Time to Act

The deadline for South Carolina’s study completion was initially sooner (November 2021), but was extended in order to match a potential North Carolina study timeline. In May 2020, associations such as our former North Carolina Clean Energy Business Alliance and Carolina Utilities Customers Association held a webinar to inform stakeholders about RTOs and develop support for developing a North Carolina market reform study.

In October 2020, North Carolina Representative Larry Strickland began working in conjunction with South Carolina Senator Tom Davis in an effort to collaborate toward bringing state market initiatives together. Strickland had already proposed a less-sweeping bill in 2019 that would have funded a general NC Utilities Commission study of competitive markets in NC, but the movement ultimately failed. Now, Strickland is planning a more detailed study proposal that aligns more similarly with the South Carolina legislation.

HB 611, filed in late April of this year, would, if passed, study the benefits and impacts of utility market reform in North Carolina. A big target of the study would be to determine if an RTO or Energy Imbalance Market are beneficial paths for the state, versus an energy exchange market like SEEM. And like South Carolina’s initiative, the North Carolina bill would examine impacts to existing interstate and interregional arrangements, the costs, benefits, and risks to all stakeholders, and how to pursue a transition with adequate equity and stakeholder input.

The Best Way Forward

After so much past contention surrounding Southeast energy market reform, it only seems natural that both North and South Carolina would run studies to get the best data on this topic—rather than jumping right into SEEM. There is also a precedent for taking the study route; for example, North Carolina has a track record of studying energy-related proposals, such as the Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Portfolio Standard (REPS) study that took place before passing the REPS law in 2007 and the Energy Storage Study completed by N.C. State University as part of HB 589.

Given that both North Carolina and South Carolina are both served by Duke Energy (Carolinas and Progress), a simultaneous and collaborative review in both states is a logical path toward market reform. There is ample data supporting some form of change in the Southeast, both in terms of customer savings, job creation, and a general transition toward cleaner energy and a cleaner economy. We are objectively laggards in the energy market space, and as we update our systems for the coming decade, it is imperative that we have the best information available and enough transparency to make the most beneficial choice for our future.

Recent Comments